I had the good fortune last week to be able to watch a dress rehearsal for

Henry V, which opens on the 16th. It got me thinking about the performance echoes that resonate in that building. I don't mean the actual quality of the sound (although our wooden space is quite nice for that as well) -- I mean the almost metaphysical residue of past performances, the ghosts floating along, superimposed over the present.

With our company, the echoes are always present in some form. It's impossible not to encounter them, especially when you see all of the sixteen plays we present each year. The cast performs in ensemble and in repertory, the same actors in different plays not just in the same season, but often returning year-to-year. When you've seen them take on dozens of roles, there are always some funny quips or interesting comparisons to draw. Watching

Henry V, however, there were two moments that struck me particularly hard. They seem to echo a bit louder than they might otherwise, thanks to the Rise and Fall of Kings series that the ASC has been producing for the past few years. The characters in

Henry V exist not in isolation, but stretching back, into the

Henry IVs, which we've produced in our Fall Seasons since 2008, and forward, into the

Henry VIs, which have been part of our Actors' Renaissance Seasons since 2009. This, I think, is the real benefit to doing the history cycles the way we've done them: the connections weave in and out of each other, creating a richer and more complex theatrical experience than seeing any one of those plays in isolation would be.

The first moment which pulled at those threads for me was almost at the very beginning of the play, in Henry's first scene, when he enters and takes unquestioned command of his surroundings. His nobles fall in ranks behind him, and he sits in the throne with full and unwavering ownership of it. Gregory Jon Phelps plays Henry for us in this production, and this scene reminded me, immediately and strikingly, of watching him play Henry VI earlier this year, in

Henry VI, Part 3 during our Actors' Renaissance Season. The visual made for a striking contradiction: bold, assured, confident Henry V versus weak, uncertain, yielding Henry VI. Henry VI never seemed comfortable in his throne, never quite gave off that aura that he

knew, in his marrow, that it was his. Henry V has no doubt. Even when he contemplates what it means to be a king, what burdens that means he has to bear, he doesn't question what he is. There's a grounded certainty to Henry V that his successor lacks. With Phelps playing both of those roles in the same year, they both, in a way, exist on stage at the same time. Trailing along beside Henry V is the faint shadow of his yet-unborn, but already-seen, son.

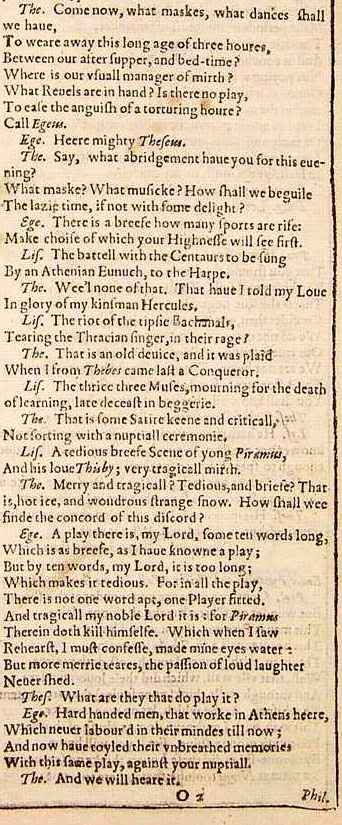

The other moment which I thought striking was Fluellen, played by James Keegan, in the following exchange:

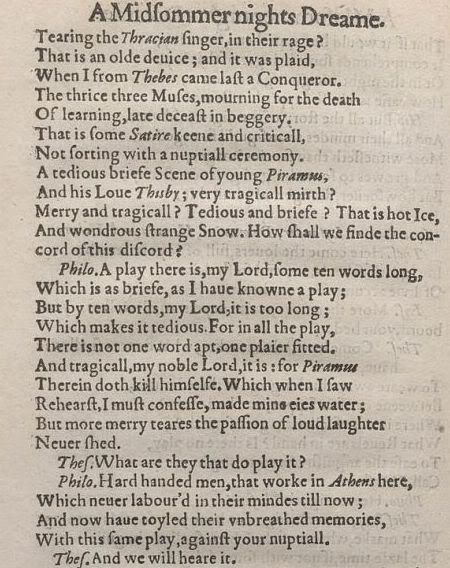

FLUELLEN

I speak but in the figures and comparisons of it: as

Alexander killed his friend Cleitus, being in his

ales and his cups; so also Harry Monmouth, being in

his right wits and his good judgments, turned away

the fat knight with the great belly-doublet: he

was full of jests, and gipes, and knaveries, and

mocks; I have forgot his name.

GOWER

Sir John Falstaff.

FLUELLEN

That is he.

There's something both sad and a little alarming there -- because, of course, Keegan played Falstaff for us the past two years, in

Henry IV, Part 1 and

Part 2, and in

The Merry Wives of Windsor. The line "I have forgot his name" would be meaningful from any actor, at least for anyone who's seen the

Henry IV plays -- because who could forget a character John Falstaff? But to have that line come from the mouth of the actor who played Falstaff, who laid down his stuffed doublet in the epilogue, saying, "This is not the man," it's somehow that much more poignant. It helps, too, that Gower is played by Allison Glenzer, who also plays Mistress Quickly (and has done in the earlier shows in this history cycle as well). The moment of vague remembrance here, towards the end of the play, recalls the earlier scene when Quickly, Pistol, Nim, Bardolph, and the Boy mourn Falstaff, weeping and laughing and telling tales. Falstaff's ghost hovers more prominently than does Henry VI's, because Shakespeare wrote the awareness of his death into the play -- but Keegan as Fluellen augments that

memento mori tremendously.

These intangible connections between shows are part of why I always hope that students will come to see us not just for one play, but over and over again -- I think if they can watch the ghosts, as I do, and see the same actors doing something completely different, they'll realize more fully how the magic of theatre lies not solely in the text, flat on the page, but in those words given life by the relationship created by an actor's skill and an audience's attention.